Yesterday I received the following tweet from the Tate Gallery in London for the inauguration of the exhibition of Sonia Delaunay that runs from April 15th till August 9th:

Yesterday I received the following tweet from the Tate Gallery in London for the inauguration of the exhibition of Sonia Delaunay that runs from April 15th till August 9th:

As #SoniaDelaunay comes to Tate we want to know: are women artists taking center stage?

Until May 10 the Tate Gallery is also hosting a major exhibition of Marlene Dumas, another artist who is enjoying impressive success in the world of contemporary art.

Both the Tate’s tweet and these two exhibitions seem to contradict my previous posting on this blog that, starting with the provocative question of the Guerrilla Girls “Do women have to strip to enter museums?” analyzes the difficulties of female artists to assert themselves in the art world. I think to understand the changes that are occurring in the role that female artists play and can play in future in art, it’s interesting to consider the artistic and personal paths of these two artists in whose lives it is already possible to find significant developments.

Sonia Delaunay-Terk was born into a Jewish family in Odessa (Ukraine) 1885. She soon moved to St. Petersburg, under the tutelage of her uncle Henri Terk, an event which would change her not only her name, but her destiny. She was hosted by a family of good social position, which offered her the possibility of a good education and particularly a strong background in several foreign languages, since it was deemed prestigious to speak French or German, even at home, among the Russian upper classes . That linguistic proficiency opened many doors to Sonia over her life and contributed to her role as a cultural agitator. From her incursions as a translator of Kandinsky’s strategic books to her relationship with the Berlin gallery Der Sturm, with which, thanks to her mediation, exhibited first her husband’s and then her own work in the years before the war.

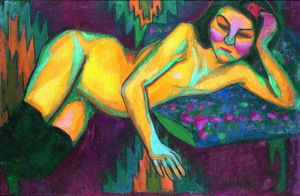

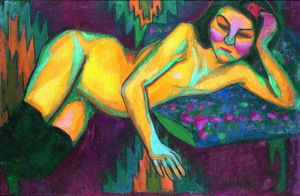

In 1904 she went to Germany. There she studied painting at the Academy of Fine Arts in Karlsruhe, training she would continue two years later in Paris, a city which opened her eyes to the color through the Fauves, especially Matisse. Through the homosexual dealer Wilhelm Uhde, whom she married in 1908 for convenience to avoid returning to Russia, she came into contact with painters living in Paris.

The direction of Sonia’s life completely transformed when she met the painter Robert Delaunay, whom she married in 1911. Together they embarked on an artistic adventure that simply was a research leading the Cubism one step further through the use of colors. Throughout their life together they created, in fact, a symbiosis in which the roles are well spaced and at the same time formed a solid whole. The pictorial art of Robert is the other side of the applied arts of Sonia, although in many cases it is she who takes the initiative, who rushes research a step further, as occurs with other famous and coetaneous couples, Hans Arp and Sophie Taeuber-Arp for example, with whom the Delaunay shared ferments and friendship at various times in their lives.

In 1913 Sonia begun to create “simultaneous dresses” which proposed the other side of her husband’s color pursuit. That challenge for the so-called “applied art” has its roots in the English Arts and Crafts movement, where a painting is not superior to the design of a dress or a vase. It is the idea of coexistence of art and craftsmanship that other artists of the time, for example Taeuber-Arp, performed with their designs of textiles, toys and tapestries. And it’s also something very Russian: the fascination with popular culture became fashionable among contemporary artists like Kandinsky.

In 1913 Sonia begun to create “simultaneous dresses” which proposed the other side of her husband’s color pursuit. That challenge for the so-called “applied art” has its roots in the English Arts and Crafts movement, where a painting is not superior to the design of a dress or a vase. It is the idea of coexistence of art and craftsmanship that other artists of the time, for example Taeuber-Arp, performed with their designs of textiles, toys and tapestries. And it’s also something very Russian: the fascination with popular culture became fashionable among contemporary artists like Kandinsky.

The year 1913 of the first “simultaneous dresses” is the same as that of a fascinating publication, a kind of book of that Sonia created with Blaise. Cendrars Siberian Prose and Little Jeanne of France appeared in Paris and was the place where the free verse of the Swiss writer met this colorful game Sonia proposes, in the style of a harlequin costume. They are the same colors of her original creations in canvas, leather, shoes, bags, dresses, coats, capes, cars … Designs that over the years Delaunay perfected qualified produced. Designs that the twenties manufactured with the Dutch stores of high range object Mertz & Co. After the owner discovered Sonia Delaunay’s work in the great International Exhibition of Decorative Arts in 1925, where the supremacy of art deco was established, the fascination, then, moved to the sophisticated mass-produced object.

In those years when she started creating her games of simultaneísmos, the home of the Delaunay in Paris became a central focus point for the avant-garde movement at which poets, writers, artists came together. Also in Madrid, where the war surprised the couple and where Sonia opened Sonia House in 1918, a design shop that dressed the aristocracy of the city, the society was fascinated by the energy of this woman.

When the war finished they returned to Paris in 1921 and Sonia and Robert Delaunay returned to being the center of attention, and their house was again a magnet for new vanguards. At that time the applied arts were as essential as the painting itself, and Sonia Delaunay was included in the exhibition of Cercle et Carré, the group formed in the in the late twenties with the aim to gather non-figurative artists. After art history would become conservative and begin to prioritize painting compared to the applied arts, fame would turn to her husband, a painter. During this period of conservative art history, Sonia was little more than a designer, a couturier and a creator of objects. Despite this the artist managed to search for the meaning of things in building the world that had some resemblance to global theater, pursuing the adventure of the colors until her death in Paris in 1979.

When the war finished they returned to Paris in 1921 and Sonia and Robert Delaunay returned to being the center of attention, and their house was again a magnet for new vanguards. At that time the applied arts were as essential as the painting itself, and Sonia Delaunay was included in the exhibition of Cercle et Carré, the group formed in the in the late twenties with the aim to gather non-figurative artists. After art history would become conservative and begin to prioritize painting compared to the applied arts, fame would turn to her husband, a painter. During this period of conservative art history, Sonia was little more than a designer, a couturier and a creator of objects. Despite this the artist managed to search for the meaning of things in building the world that had some resemblance to global theater, pursuing the adventure of the colors until her death in Paris in 1979.

The Tate Gallery exhibition is the first retrospective in the UK to assess the magnitude of her vibrant artistic practice through a wide range of media. It will be exhibit her innovative paintings, textiles and clothing made through a sixty-year career, and also the results of her innovative collaborations with poets, choreographers and producers, from Diaghilev to Liberty.

Marlene Dumas is a South African artist, born in Cape Town in 1953. During her childhood she lived in Kuilsrivier, South Africa where she spoke Afrikaans, her mother language. She grew up in the world of apartheid, closed to the outside world, with some pictures in books or magazines as a small window to the outside world. She graduated in Visual Arts at the University of Cape Town in 1975 and, thanks to a scholarship, she moved to live in the Netherlands to become a free artist but never completely breaking the umbilical cord with her homeland. “South Africa is my content” she says.

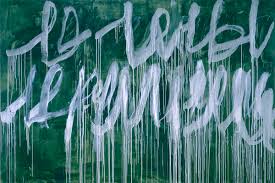

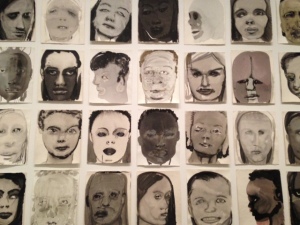

From 1976 to 1978, she worked imparting education in Ateliers ’63, Haarlem and in other Dutch institutes. She devoted herself to represent scenes or figures from files of own photographs, newspapers and magazines. The starting point of her work is almost always a picture, sometimes taken by her, sometimes clipped from a magazine, which then transforms into a painting. Along with painting, often subtle and watery, like rain which allows to glimpse the canvas, Marlene Dumas adds to the simple initial image a strong charge interpretive and emotional. Her paintings are not decorative: they are strong works which affect the eyes and capture the mind and the imagination. The news is elevated to emblems of a condition or situation. The role of women in history has always fascinated Marlene Dumas. An Algerian patriot captured by police during the war of independence in 1961, the German terrorist Ulrike Meinhof dead in prison, a victim of Chechen terrorism, a Palestinian terrorist, the wife of the killed African leader Patrice Lumumba, including Charlotte Corday, the assassin Marat, who before being guillotined said she had “killed a man to save one hundred thousand”: each merits a painting.

From 1976 to 1978, she worked imparting education in Ateliers ’63, Haarlem and in other Dutch institutes. She devoted herself to represent scenes or figures from files of own photographs, newspapers and magazines. The starting point of her work is almost always a picture, sometimes taken by her, sometimes clipped from a magazine, which then transforms into a painting. Along with painting, often subtle and watery, like rain which allows to glimpse the canvas, Marlene Dumas adds to the simple initial image a strong charge interpretive and emotional. Her paintings are not decorative: they are strong works which affect the eyes and capture the mind and the imagination. The news is elevated to emblems of a condition or situation. The role of women in history has always fascinated Marlene Dumas. An Algerian patriot captured by police during the war of independence in 1961, the German terrorist Ulrike Meinhof dead in prison, a victim of Chechen terrorism, a Palestinian terrorist, the wife of the killed African leader Patrice Lumumba, including Charlotte Corday, the assassin Marat, who before being guillotined said she had “killed a man to save one hundred thousand”: each merits a painting.

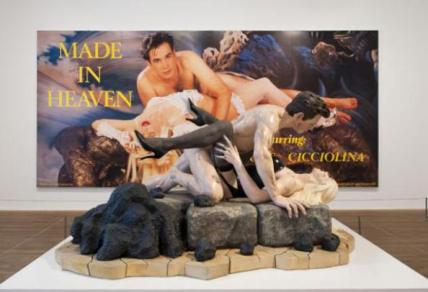

Marlene Dumas is a figurative artist, almost all her paintings are portraits of people or anyway focused on the human figure. There is no background, no scenery, no point of view, everything is focused on the expression of the faces or on the importance of gestures. However the expressive power of her art doesn’t require human features, as evidenced by the extraordinary picture Mindblocks: stone blocks that give an immediate feeling of anguish, but a glimpse of escape. There is hope, as long as we let go our “mental blocks” and liberate the imagination.

Marlene Dumas is a figurative artist, almost all her paintings are portraits of people or anyway focused on the human figure. There is no background, no scenery, no point of view, everything is focused on the expression of the faces or on the importance of gestures. However the expressive power of her art doesn’t require human features, as evidenced by the extraordinary picture Mindblocks: stone blocks that give an immediate feeling of anguish, but a glimpse of escape. There is hope, as long as we let go our “mental blocks” and liberate the imagination.

The exhibition at the Tate Modern condenses the integrity of a trajectory that began in the seventies, owing to her now becoming one of the most respected names in art today as well as one of the most quoted. In 2008 she became the most expensive living woman artist when someone paid 4 million euros for a canvas entitled The Visitor. Five years before, her works were sold for 20,000 euros. There was something in her dark expressionism which began to resonate in her time. It Marlene Dumas bothers to remember this fact, perhaps because this debate diverts attention from the contents of a complex and fascinating work, like an enigma that one faces a thousand times without finding a solution, which she talks of as her most prized possession.

In the end the artistic and personal paths of these two great artists show us the way that artists, not only female, have to establish themselves is by leaving their small environment and measure themselves against the world at large without forgetting their roots, which always will influence the form of their artistic expressions. For women it has always been more complicated but Sonia Delaunay and Marlene Dumas, at different times, have attained this result and their exhibitions in London confirm it.

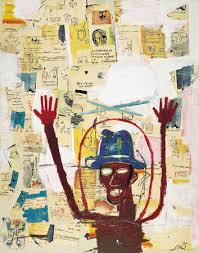

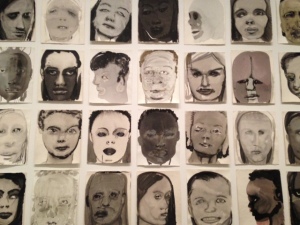

The artist’s portraits, in a strange way, communicate they’re not to be trusted. And for good reason. The images, rather than highlighting specific individuals in time and space, conjure fictitious presences, people that never were, outside of the realm of canvas and paint. The artist uses no photographs or preliminary sketches to create her startlingly realistic portraits. The detailed depictions are concocted entirely in the imagination, and executed in paint during the course of a single day.

The artist’s portraits, in a strange way, communicate they’re not to be trusted. And for good reason. The images, rather than highlighting specific individuals in time and space, conjure fictitious presences, people that never were, outside of the realm of canvas and paint. The artist uses no photographs or preliminary sketches to create her startlingly realistic portraits. The detailed depictions are concocted entirely in the imagination, and executed in paint during the course of a single day. within the ranks of historical painting. With Yiadom-Boakye’s layering of references, her paintings draw attention to the flawed perception of race in historical paintings. In depicting black subjects doing everyday things, she advocates both the normalcy and intricacy of blackness.”

within the ranks of historical painting. With Yiadom-Boakye’s layering of references, her paintings draw attention to the flawed perception of race in historical paintings. In depicting black subjects doing everyday things, she advocates both the normalcy and intricacy of blackness.”